IDE Not Required

Jan 26, 2026 - Portland

We are currently navigating a phase of technology with coding agents that has been described as “receiving an alien artifact without an instruction manual.” We are all figuring it out through trial and error, with mixed outcomes, and sharing anecdotes about our techniques and intuition developed in a private setting, just us and the machine.

This is my attempt to articulate the mental model and intuition that has worked for me. It’s not a rigorous framework—just practitioner notes that I’ve found useful for thinking about agent workflows.

Instead of writing code, our job has shifted to two new activities: Providing Sufficient Information and Enablement.

Part 1: Theory

We need to step back and ask: What are we actually doing when we ask an agent to code?

For coding & software development tasks we are searching document space for an acceptable solution.

We are not looking for Hamlet.

We are not taking draws from a uniform distribution.

But we know a program that will solve our reasonable problem is probably out there.

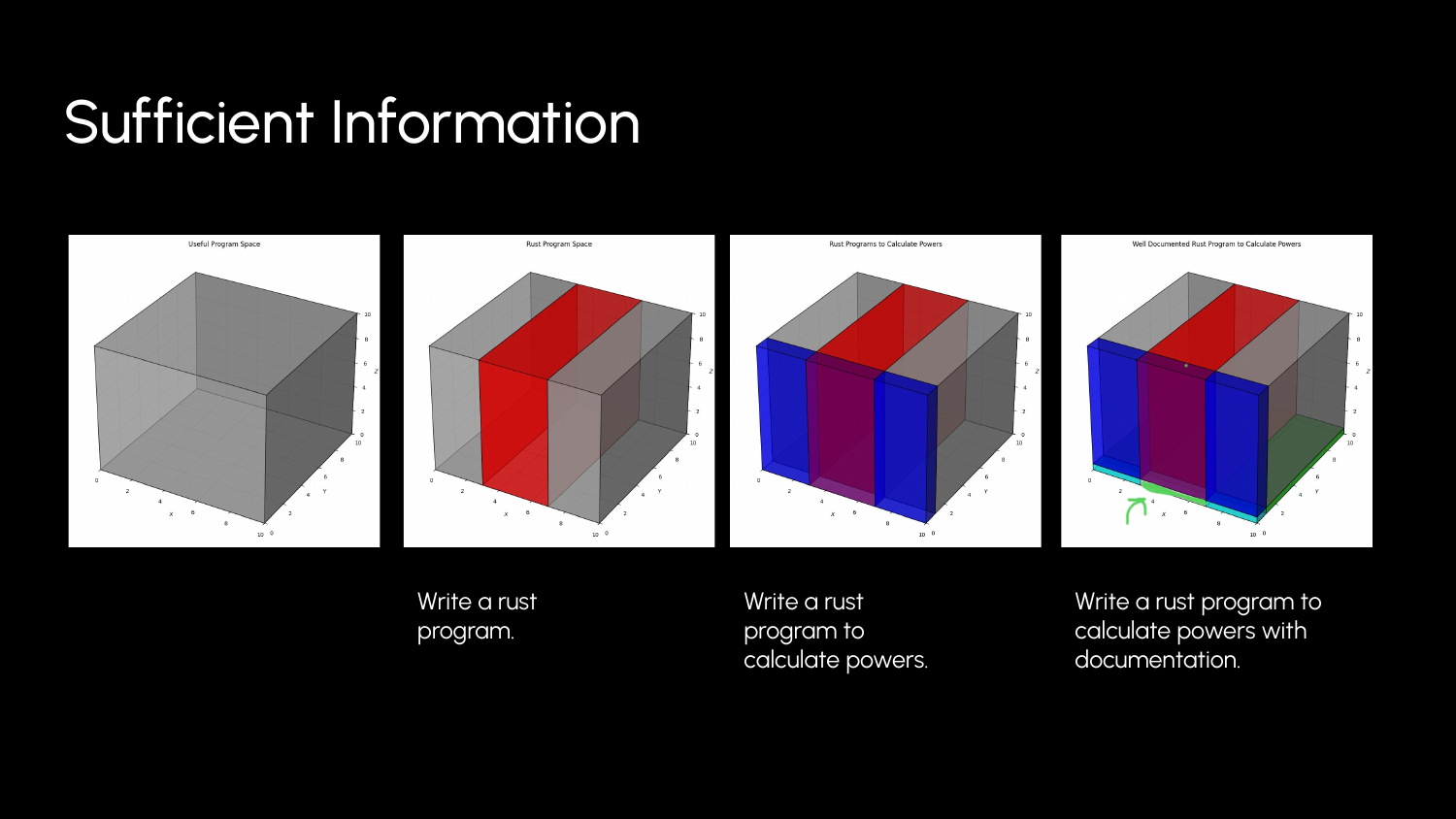

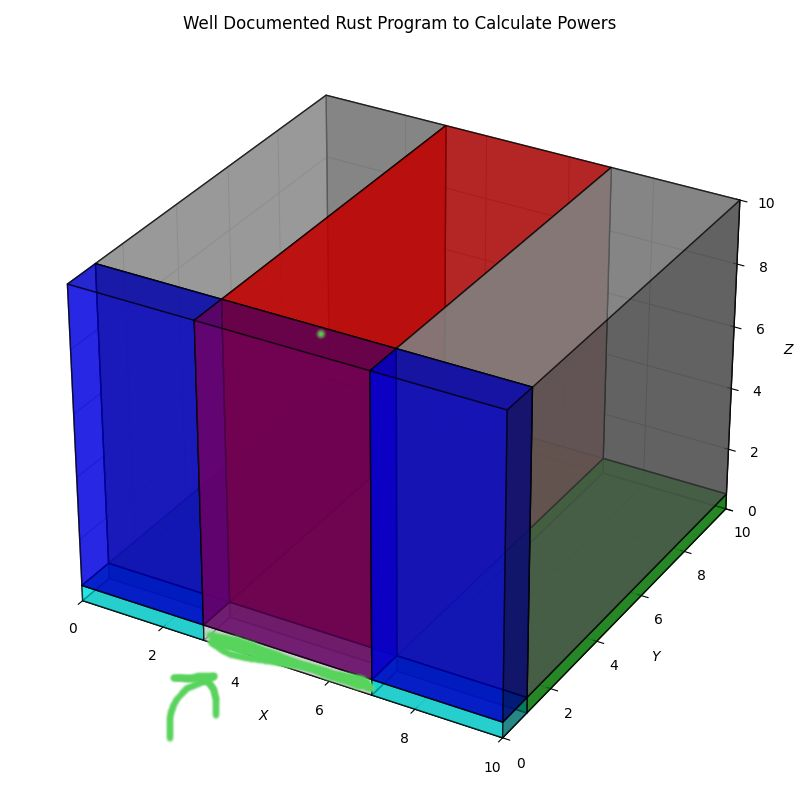

The Document Space

Imagine a “Document Space”—the set of all possible character sequences that could be a program. This space is astronomically large. But the space of programs an LLM will actually generate is much smaller, constrained by patterns in its training data. Your job is to narrow it further toward your actual goal.

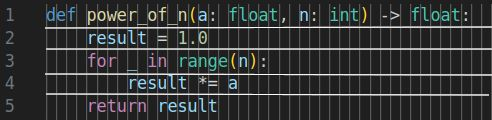

Here’s a random draw from the space.

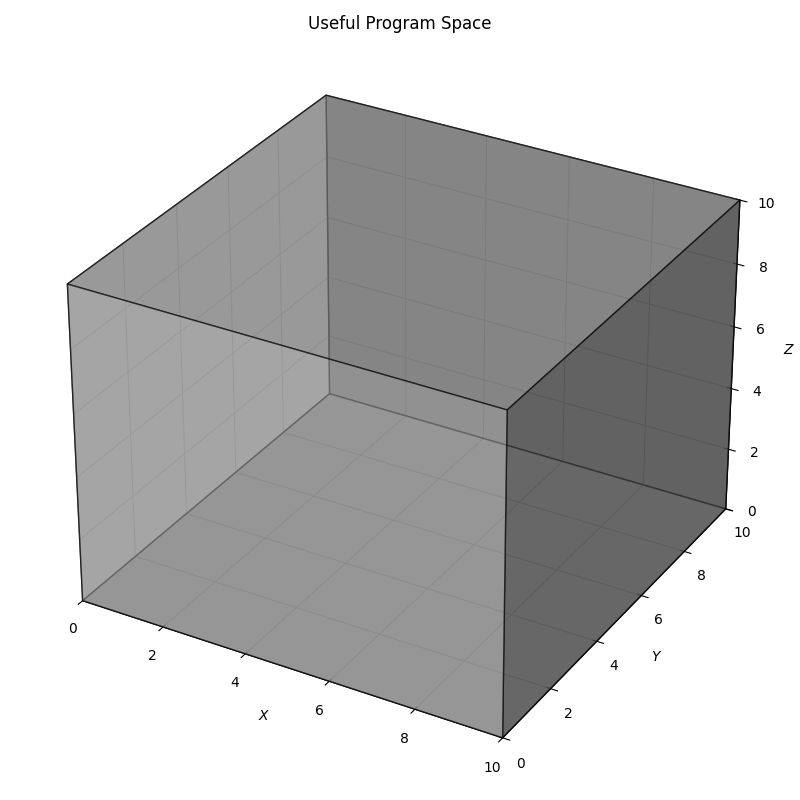

Useful Program Space

The model’s weights restrict outputs to plausible text—it has seen lots of software. So we can imagine a much smaller Useful Program Space.

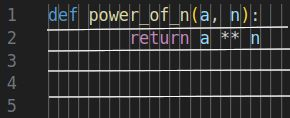

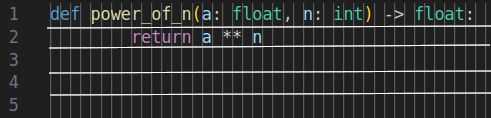

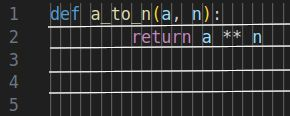

We are trying to find a single member of a relatively small set of these points that complete our task. For the problem of finding $a^n$ we might draw some samples from this space like the following. Note that these are all acceptable solutions and that there are many points that are equivalent.

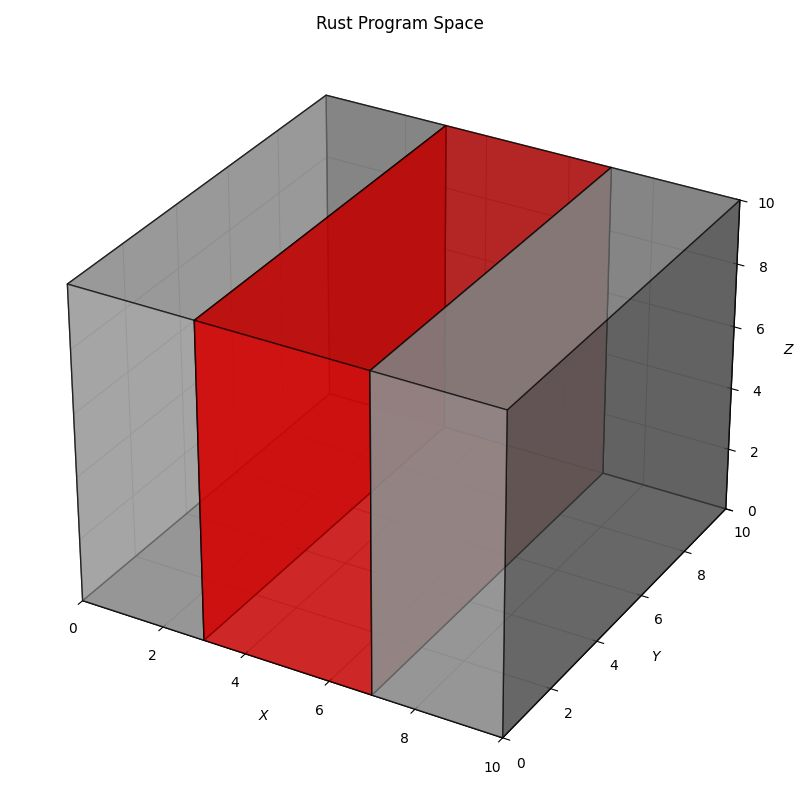

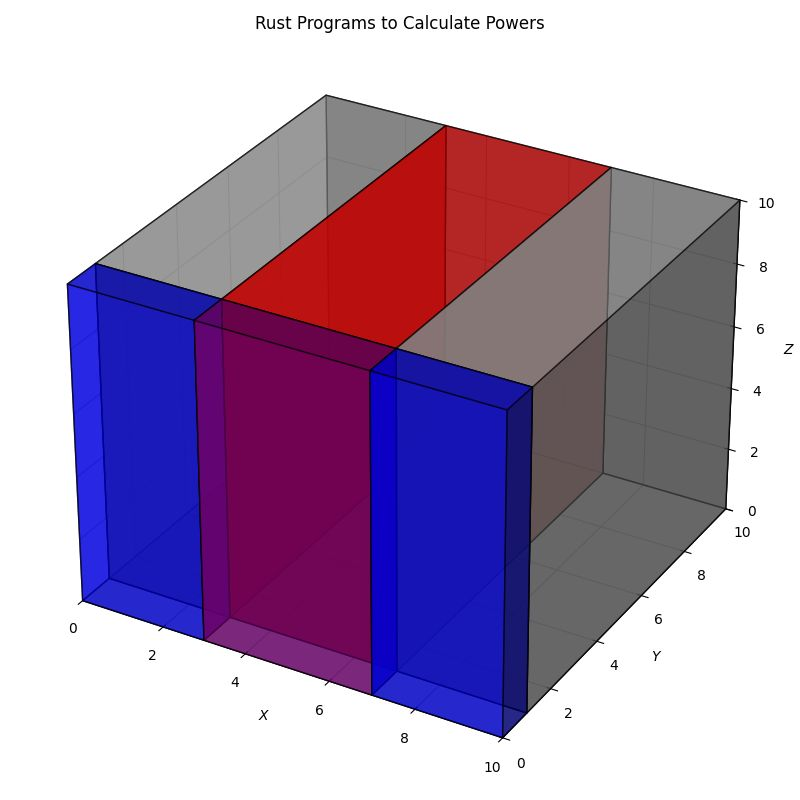

Magic Projection

Now consider a magic projection that keeps programs localized by semantics.

The intersection in the diagram above represents the set of character sequences that solve your specific problem. Our goal is to land in that intersection.

The “20 Questions” of Sufficient Information

Think of the game “20 Questions.” If I am thinking of a specific object, and you ask broad, vague questions (“Is it a thing?”), you gain information (bits) to narrow down the search space.

In our context, the “game” is cooperative. You are providing descriptive statements to help the agent guess an acceptable point in the Useful Program Space.

- Low Information: “Write a rust program.” (Millions of valid answers, most useless to you).

- Medium Information: “Write a rust program to calculate powers.”

- Sufficient Information: “Write a rust function

pow(a, n)that takes two integers and returnsaraised ton, handling overflow by returning aResulttype.”

Missing Information

When we leave out a detail, we take a draw from the system’s distribution.

Sometimes that’s fine. You don’t care about the variable names. You want to see what good approaches the system has learned. Sometimes it’s fatal (you didn’t mention a surprising detail about the database schema).

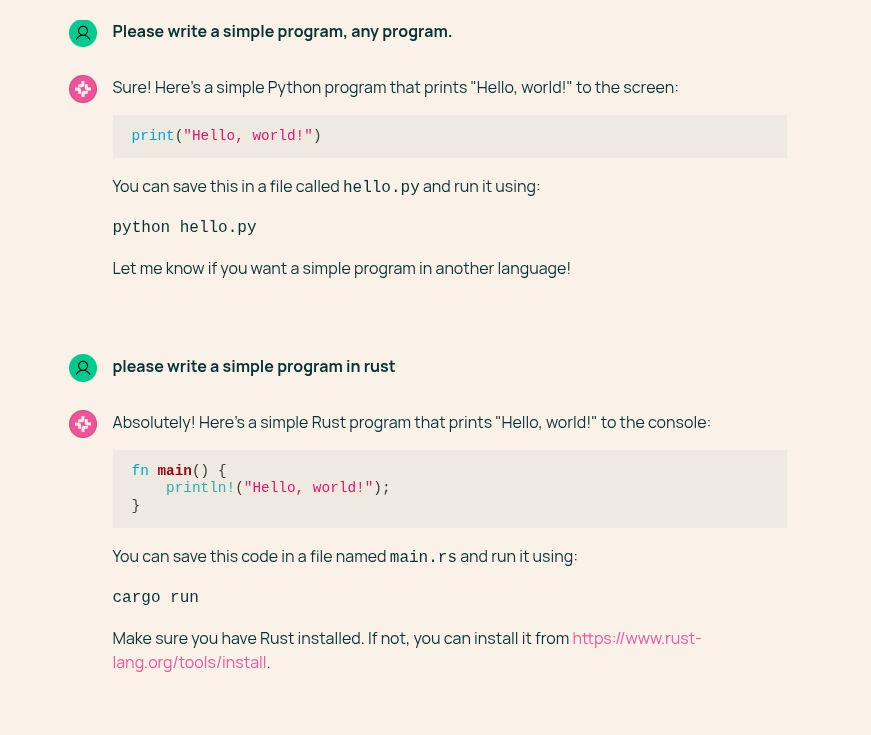

Intuition Check

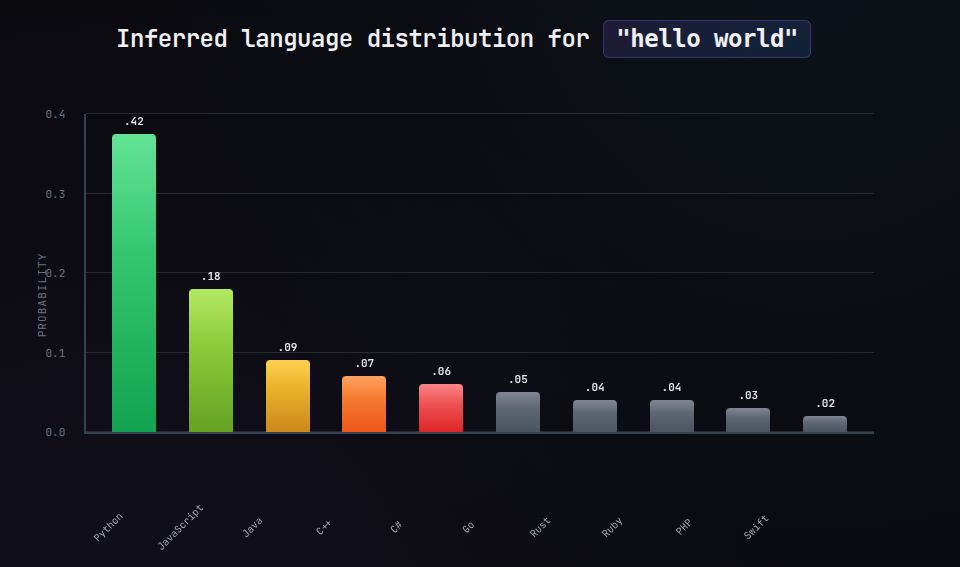

Take a moment to check your intuition, what would you expect from a prompt with minimal information, “Please write a simple program.”

What do we get? “Hello world” in Python.

But oops, we actually wanted it in Rust.

There are a handful of critical bits we left out. Because our goal is somewhat surprising, relative to the distribution of programming language documents the model has seen, we need to include that information.

This is a loose analogy, but I find it useful: if you’re communicating with a machine to play a variant of 20 Questions, you’ll play better if you tap into your basic intuition about how information narrows possibilities.

Enablement

The second pillar of the theory is Enablement. We want to enable the agent to complete our task without our further participation.

Loading the Machine To achieve longer runtimes and complete autonomy, we must provide:

- A Complete Plan: (Sufficient Information)

- Context Engineering: (Tools & Access)

- Acceptance Criteria: (Objective measures of success)

When you combine a complete plan with the appropriate tools, you remove yourself from the loop. The agent can draft a solution, test it, fail, read the error, and retry—looping until it satisfies the acceptance criteria you provided.

Part 2: The Practice

So how do we apply this? By rigorously practicing Not Writing Code.

1. Planning

I’ve found myself spending far more time on planning than I expected—often more than on the execution itself. Most coding agents have a “Plan” mode in which you can develop a document that outlines the high level details of how to approach a task.

Don’t skip this.

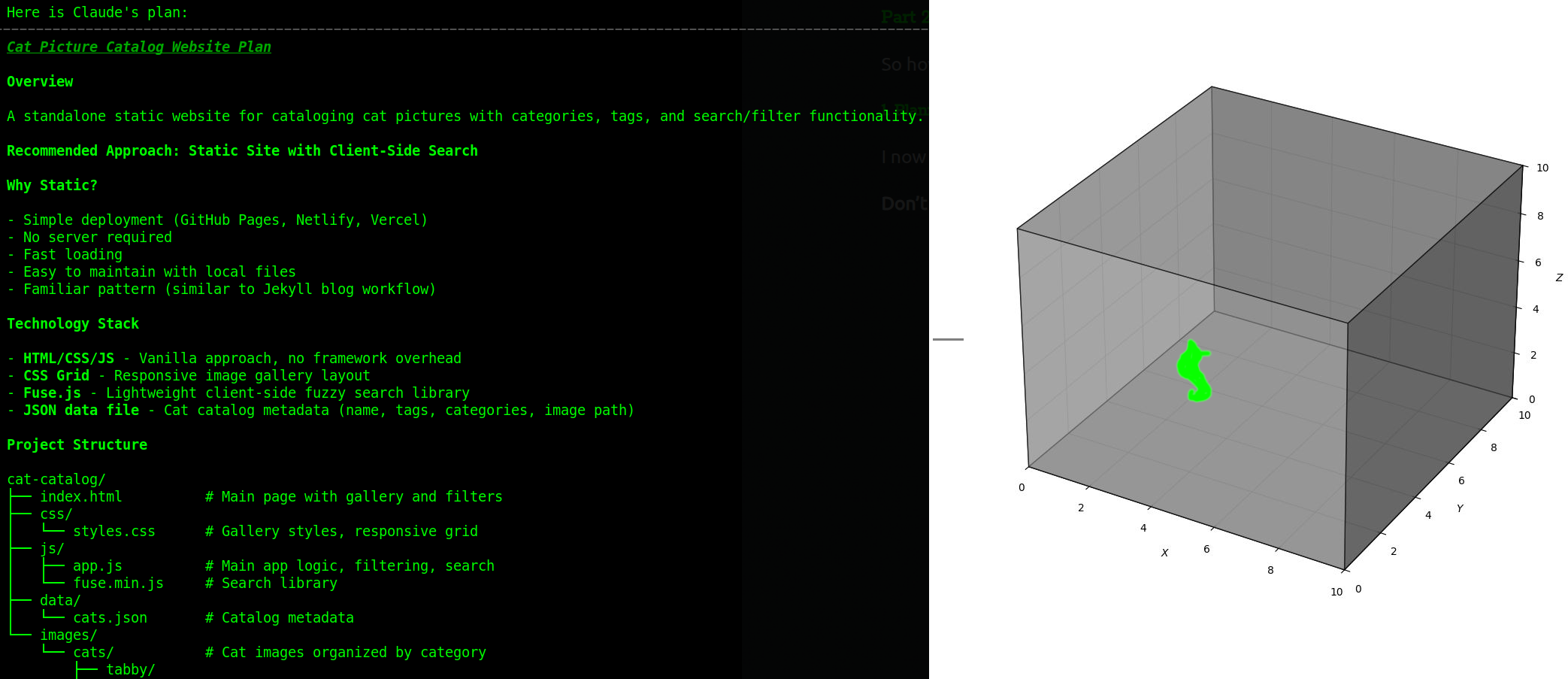

Here is a plan for a website that catalogs cat pictures and a whimsical display of how this plan restricts the set of programs we might draw.

A plan is a preview of the “draw” the agent is about to take. It tells you how the agent has interpreted your request. If the plan says “I will add a new column to the database” and you wanted a runtime calculation, you catch it here—before a single line of code is written.

The Iterative Process

It is not unusual to have 20+ interactions just to form a plan. This is where the work happens.

- Start with a short description.

- Ask the agent to research the codebase.

- Refine the plan.

2. Incorporation

You are not the only source of useful bits to identify an acceptable solution. The agent isn’t omniscient. It only knows what you show it.

- Explicit References: Don’t just say “check the auth logic.” Say “Check

@auth/middleware.pyand@auth/utils.py.” - Docs: If you are using a specific library, paste the relevant documentation or URL into the context. “See

https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/reference/.”

Print Debugging: Nudging towards information

When the plan fails (and it will sometimes), return to planning mode.

- Describe the problem: Paste the error message and the debugging session.

- Theory: Provide your theory if you have one.

- The Prompt: “Please add debugging statements to identify the root cause. Run

<specific command>and review the output.”

This is Incorporation: You are adding sufficient information (runtime state) to the context so the agent can find the solution.

I look forward to the day when execution tracing is completely nailed down. I am also waiting for agent providers to add a subagent functionality that creates a throwaway branch, adds logging, and executes the code.

3. Enablement & Context Engineering

This is a critical shift. You must enable the agent to close the loop itself.

By default, agents have a set of generic tools: Bash, Read, Write, Edit, Glob, Grep.

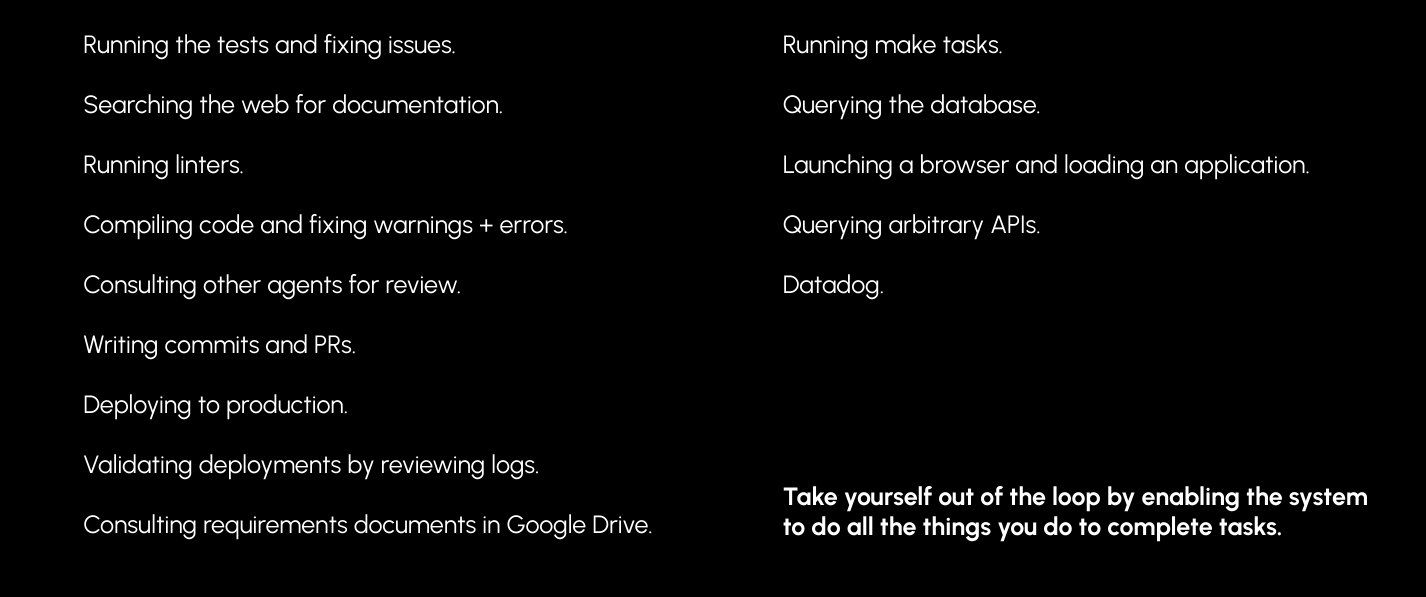

Enablement takes many forms: running tests, searching the web, running linters, compiling code, deploying to production, or consulting requirements documents.

But the crux of it seems to be arbitrary Bash. If the agent can execute shell commands, it can do almost anything you can do. Your job is to engineer the context so it knows how to use that power effectively.

The Context File

Create a Gemini.md or Claude.md file in your root to give the agent the instruction manual for your repo.

# Project Instructions

## Running Tests

This project uses pytest.

- Run all tests: `pytest`

- Run specific test: `pytest tests/test_auth.py`

- Note: The database must be running (`docker-compose up -d db`) before tests.

## Linting

- Check style: `flake8 .`

- Fix style: `black .`

## Common Tasks

- Start server: `uvicorn main:app --reload`

- Database migration: `alembic upgrade head`

When the agent can run the tests via Bash, read the error output via Read, and try again, you have successfully removed yourself from the “Compiler -> Human -> Fix” loop.

4. Verification

Just like with artisanal code, we are concerned with correctness, performance, and maintenance implications. We verify agent-produced code much like we verify normal code—through tests, benchmarks, and review.

- Correctness: This is the baseline. Do the unit and integration tests pass? Does the feature work as expected in the high-level acceptance tests?

- Performance: Agents are generally not great at writing performant code. To be fair, maybe the average GitHub repo isn’t great either. You should pay extra attention to any situation where performance matters, and sometimes you just have to “wait for better models.”

- Maintainability: Agents are also not great at this. Review and provide information about maintainability changes or try the Anthropic code simplifier.

Manual Code Review

Of course, you can still look at the diff. But we are on an imposed spiritual journey to let go of reading the code. There’s just too much code to review.

Traditional manual code review is the ultimate bottleneck in a multitasking world; it is simply too time-consuming. The goal is to reach a point where you trust your Verification Criteria enough that you only dive into the source when something breaks.

Advanced: Multitasking

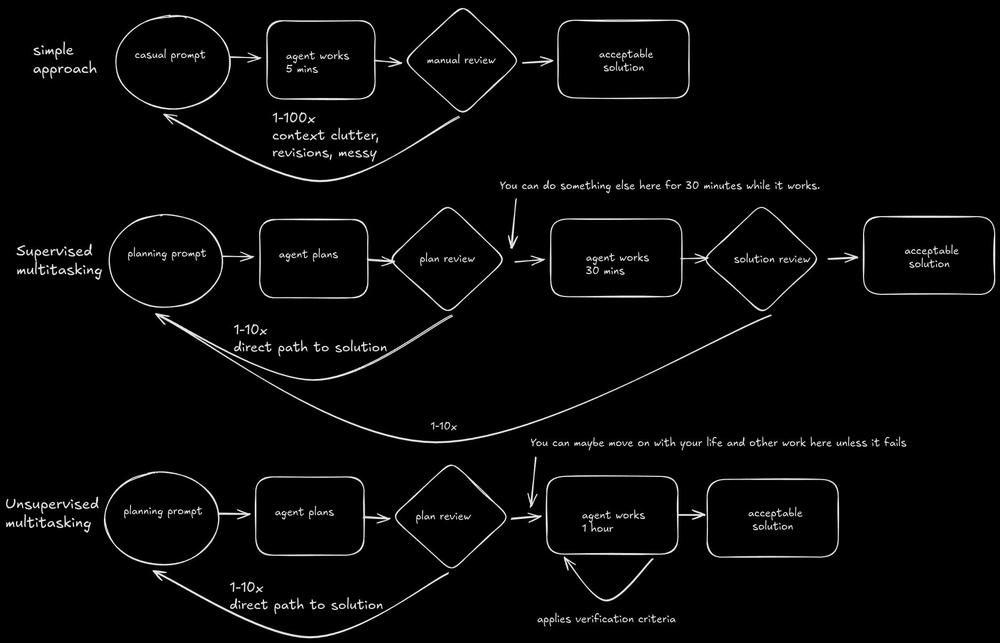

Once you trust the Plan -> Enable -> Verify loop, you can start multitasking.

Supervised Multitasking

I’ve found two concurrent complex tasks reasonable, but beyond that it becomes difficult to keep the necessary context in your own head.

Git Worktrees make this easy—multiple branches checked out in different directories, each with its own agent. For a deep dive, see the Anthropic guide on Git Worktrees.

- Task A: Spend 15 mins planning. “Go implement this, run the tests until they pass.”

- Switch to Task B: Start planning.

- Check Task A: Tests passed? Great. Merge. Tests failed? Provide a hint and send it back.

Unsupervised Multitasking (“Fire and Forget”)

As agents improve at mapping plans to solutions, the need for review declines.

Ultimately, agents just need to know the acceptance criteria and be enabled to check it. I’ve experimented with using sub-agents to apply verification criteria or to check a plan for the presence of acceptance criteria, but I’ve found that simply including the criteria in the original plan is often good enough.

There’s currently a lot of activity in the world exploring what the future of managing many agents will look like. Here’s a cautionary example:

In this example, what information is provided to discern the region we are drawing from?

Just the word “app”. That’s a great way to generate print("hello world") with just a few simple clicks!

While I admire the direction and anticipate some very cool UIs for keeping track of work, there is an irreducible need to supply sufficient information to describe your solution.

Conclusion

The future of software engineering isn’t typing characters into a text buffer. It is:

IDE not required.